|

| Illustration only, not for sale |

Just write your name in it - This is the simple version of the complex relationship between humans and their books. Because of the general movability of books (

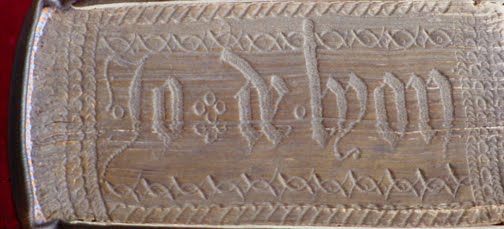

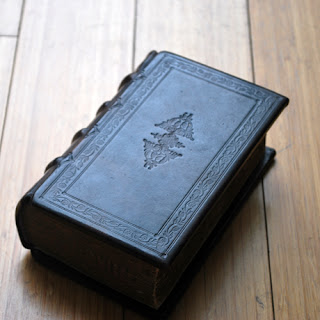

have you seen these tiny feet!) the documentation of ownership is not trivial. Mixed into this is a desire for display and status that manifests itself in the way a book is owned. The binding, typically created to the specifications of the owner, is a prime opportunity to manifest ownership. With the mark of the owner, one tries to nail the book to this shelf and to end the general flux of books from hand to hand, wandering from shelf to shelf. Grolier, a contemporary of our Jo de Lyon, marked the books of his library with a generous "

et amicorum" thus confirming the delicate balance of display and ownership, something the modern term "

conspicuous consumption" conveys. In this manner the

royal bindings on the left are not about securing property, but a way to display ownership and status.

These are signed bindings, not in the sense of carrying the name of the binder, but because they carry the name of their owner.

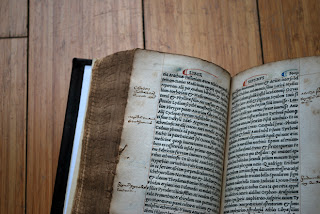

In keeping with the contemporary practice of storing books flat, a bit of ink (examples below) can do the trick too. Inscribing the title of the book, or the name or initials of the owner on the edges, was part of the behavioral repertoire of owning a book.

What is happening along the edges is considered part of the binding, an area which deserves further study. Our book is also creating meaning on the book edges, but on an altogether different level. For all we know,

E.A.M. could be a schoolboy, and

Jo de Lyon could be a king. He instructed